Fake News In History 2: After the Printing Press

Fake news isn’t a new phenomenon, but it has changed a lot over time. These lessons will take a dive into the history of news and fake news up until the rise of the internet.

In this lesson, students will learn about news and fake news since the invention of the printing press. They will also analyze three different case studies from different historical periods.

In the next and final lesson, students will do a fake news simulation in which groups create different narratives based on the same facts.

Lesson goals

- Learn about the impact of the printing press

- Understanding more about the impact of the Reformation on the way people relate to information

- Fake news story analysis

Activities

Theory (10 minutes) - Teacher-centered

Present the theory to the students.

Aim: Students learn about the invention of the printing press and how it impacted the circulation of information, literacy, and power structures.

Exercise (20 minutes) - Smaller groups of 2-3

Students answer the exercise questions for the three of the five stories. They are encouraged to do additional research.

Aim: Students do research to analyze historical fake news stories.

Discussion (15 minutes) - class

Discuss the answers to the exercise questions with the class.

Aim: Students share their thoughts and learn from each other’s insights.

Discussion questions (optional) - class

Discuss the discussion questions with the students.

Aim: Students reflect on the subject.

Keywords

Theory (10 minutes)

The printing press

The invention of the modern printing press by Johannes Gutenberg in 1439 made it cheaper and faster to print text. Rather than having to write everything by hand, which cost a lot of time and money, machines produced more copies using less resources.

In the beginning, books were still very expensive and printed for political and religious elites. Texts were usually published in Latin rather than local languages. Regular people didn’t have access to reading materials or education (in Latin), so the illiteracy rate was very high.

The Reformation and literacy

An important push toward literacy came with the Reformation in 1517, when Martin Luther challenged the Catholic Church and the papacy. In the following decades, he translated the Bible into German so that people could read the texts for themselves. The printing business was booming during the Reformation, resulting in more than ten million copies of ten thousand different publications by 1530—only 13 years after Luther’s protest.

The Catholic Church didn’t just sit back and watch during the Reformation. As an important gatekeeper of the news, politics and religion, the newly popularized printing press was a threat to the Church’s power. The printing press was used by reformers to mass produce ideas that challenged the Church, and the political leaders that supported (and were supported by) the Church.

In Martin Luther’s case, many religious scholars tried to convince him that his ideas were wrong. When Luther didn’t budge, he was excommunicated from the Church in 1521. The Reformation triggered a wave of Catholic publications refuting the reformers’ ideas and reaffirming the truth of the Catholic faith. In the meantime, the revolutionary protestant ideas were gaining popularity by the day, weakening the Church’s position as a gatekeeper of information.

The protestant texts became so popular that many monarchs and religious leaders started banning them altogether. Their explanation was that sharing protestant ideas was like spreading what we now call “fake news” about God, the Church, and the nature of reality.

The city of Leipzig, which was an important publishing center at a time, experienced such a ban in 1524. Seeing a significant part of their income disappear, local printers voiced their discontent about the ban and moved to more tolerant cities or continued printing protestant texts in secret.

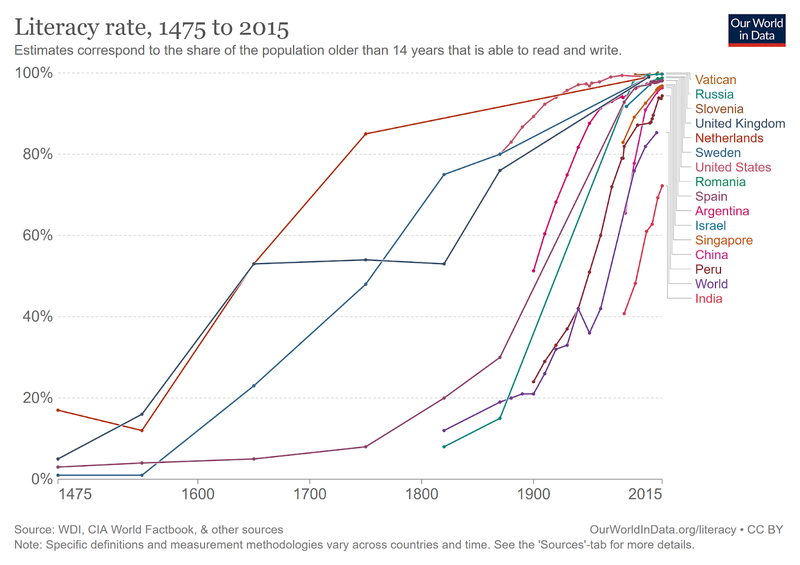

Although some countries (modern Sweden, Finland, Latvia and Estonia, of whom the first two followed the Lutheran faith) started enforcing literacy on their people from 1686 onward, global literacy started steadily increasing by the 1900s.

https://ourworldindata.org/literacy#historical-change-in-literacy

Publishing and power

As technology advanced, printed texts became ever-cheaper, even leading to the self-explanatory Penny Press in the 1830s in the United States—newspapers that cost just one cent.

Increased affordability and literacy made the world of publishing more democratic, too. No longer was publishing a privilege of kings and Bishops for their law-making and propaganda. The written words became more accessible, and news, literature, critique, science, and ordinary life started flourishing.

A thriving publishing landscape created room for people to share their thoughts and discontents. Like Martin Luther, critics could use their writing to oppose the church or other powerful institutions and leaders. This could be done directly, by speaking out against them, or indirectly, through satire. The press gained ground as a platform to spread news and inform people about the goings-on in the world. Simultaneously, access to the tools to spread fake news became available to a wider group of people.

Although far removed from today’s capacity to spread (dis)information through the internet, the printing press fundamentally changed the relationship between information and ordinary people.

Five fake news affairs after the printing press

1700s—The king who fell ill

King of Great Britain and Ireland George II fell ill while trying to squash the Jacobite rebellion against him. Or did he? The invention of the printing press had made it easier to spread news, and had also made it easier for his adversaries to spread fake news about him. Rebels tried to dismantle the image of King George as a strong leader by publishing stories about the king being sick when he wasn’t. Although the rebellion ultimately wasn’t successful, the news spread like wildfire.

1782—Franklin versus Native Americans

In 1782, Benjamin Franklin created a fake issue of an existing Boston newspaper, in which he fabricated a story about Native Americans sending scalps of hundreds of colonists to the King. This story was treated as fact and reprinted many times, creating public outrage.

1835—The Great Moon Hoax

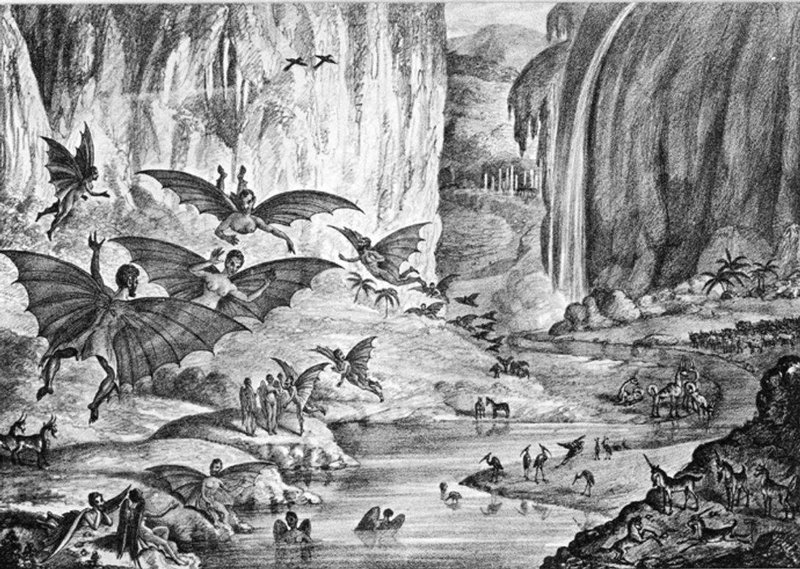

Newspaper The New York Sun published a series of articles about the discovery of life on the moon by a famous astronomer named Sir John Herschel. But, as we know, Sir John Herschel had discovered no such things.

Newspaper sales skyrocketed as people wanted to find out more about the unicorns and bat-men in space. Although the stories were written as satire—an exaggerated story to make people laugh—plenty of people believed it was true.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Great_Moon_Hoax#/media/File:Great_Moon_Hoax_-_Day_4.jpg

1917—Dead Soldier Soap

During the First World War, some British newspapers reported that the Germans were making soap and margarine out of the fat of dead soldiers’ bodies. The news originally came from the British government, that had paid writers and publications to circulate the story.

Wouldn't it be incredible to turn HG Wells' science fiction novel The War of the Worlds into a radio play, thought his near-namesake Orson Welles. The relatively new technology could really help people immerse themselves in a story. This proved to be true.

When the story about an invasion from Mars was broadcast, people started panicking and reportedly took to the streets by the thousands, newspapers reported the next day.

Only this had not happened. The broadcast had certainly fooled some people, but there had been no mass hysteria or thousands of people running in the streets.

Exercise (20 minutes)

The stories have something in common: all of them contain elements of fake news.

- Students are divided in groups of 2-3

- Groups choose 3 of the 5 case studies to analyze

- Groups answer the following questions about the case studies they picked. They are encouraged to do extra research to answer the questions.

- Who was spreading the story?

- How were they spreading the story?

- What goal were they trying to achieve by spreading this story?

- Who believed the story, and why were they convinced?

- What effects did the spread of the story have?

- Did those who spread the story achieve their goals?

Discussion questions (optional)

- Why did the printing press make the reproduction of text cheaper and faster?

- How do the printing press and literacy relate to each other?

- What did the Catholic Church like and dislike about the printing press?

- Why were the ideas and works from the Reformation so popular despite being banned in many places?

- Did the printing press increase or decrease the spread of fake news?