Fake News In History 1: Before the Printing Press

Fake news isn’t a new phenomenon, but it has changed a lot over time. These lessons will take a dive into the history of news and fake news up until the rise of the internet.

In this lesson, students will learn about news and fake news in ancient history and, more importantly, before the invention of the printing press. They will also analyze three different case studies from different historical periods.

The next lesson will look at fake news after the invention of the printing press.

Lesson goals

- Learn about news before the printing press

- Learn about the relationship between power and the creation and dissemination of information.

Activities

Theory (15 minutes) - Teacher-centered

Present the theory to the students.

Aim: Students learn how news spread in ancient times and how it related to power structures.

Exercise (20 minutes) - Smaller groups of 2-3

Students research and answer the exercise questions for one of the three stories. They are encouraged to do additional research.

Aim: Students use the theory to analyze historical anecdotes.

Discussion (10 minutes) - class

Discuss the answers to the exercise questions with the class.

Aim: Students share their thoughts and learn from each other’s insights.

Discussion questions (optional) - class

Discuss the discussion questions with the students.

Aim: Students reflect on the subject.

Theory (15 minutes)

The dawn of information

Figuring out how to draw and write, humans unlocked a new way to communicate over space and time. It may be easy to get your message across to someone who is in the same room—if they speak the same language—but speaking to someone who is far away comes with its challenges without a mobile phone.

Registering information using language changed the way humans communicated forever. It enabled them to plan ahead more, settle on agreements, and jot down memories. And with this new technology came a new form of power. The power to create, control and share information.

This power was not for everyone. Think about the ancient Egyptians. You may have heard of Ramses, Tutankhamun, or Cleopatra. All of these people were royalty, the kings and queens of a great civilization that lasted about 3000 years. By portraying themselves as powerful and potent people, ancient leaders hoped to convince the common people to accept their rule. Yet we don’t know much about the “normal people” in Ancient Egypt. The power to be remembered—writing things down, commissioning art, or building tombs like pyramids—was in the hands of the rulers.

Ancient fake news

The story of fake news begins when people learned they could manipulate information in their favor. We have all done this to some degree: to retell something you are not proud of in a way that makes it sound a little better. To make yourself a hero in a story where you really weren’t, maybe. But in the realm of emperors and empires, an altered truth could change the course of history.

Ironically, the writings on clay tablets or scrolls chronicling ancient leaders’ stories are one of a handful of resources we have to understand history. No other sources, like archeological artifacts or geological data, tell as many details as a text. That is why historians refer to the period before writing was invented as “prehistory”—the time before recorded history started.

How to spread the word

Spreading information before the printing press or the internet was a lot more challenging than it is today. Rulers in the past used a bunch of different methods to spread the word. Although these were useful starting points for news to spread, however, people would primarily receive their news through word of mouth.

Messengers

Ancient Persia used a network of stations a day's journey apart when traveling by horse. Riders, called the angaros, carried the messages from station to station, enabling a message to travel 2699 kilometers from Susa to Sardis in 9 days.

Merchants, traders, and travellers

People on the move carried more with them than just goods and were an important source of information in ancient times.

Art

Nowadays, you may revisit your phone’s camera roll to relive some precious memories. In the past, leaders prefered to enlist the help of artists to register their memories—and even improve them a little in the process. For example: Egyptian wall paintings and engravings, covering topics like religion, warfare, and people working.

Heralds and town criers

Picture someone standing on a box in the market square, yelling. This was the job of heralds or town criers, often on behalf of political authority or religious leadership. Heralds in ancient Rome were known to make announcements on market days.

Clay tablets

In the Roman Republic, news was also inscribed on clay tablets called Acta Diurna (or “daily doings”) that were put in the Forum (central square) of Rome. Later, these tablets were stored for record keeping.

Messages on coins

Ever wondered why coins show the face of a king or queen? Ever since coins were first used in Anatolia in the 7th century BCE, they were used as a way to let people know that a new ruler was in charge. Additionally, people in power would mint coins to spread other messages throughout their empire.

Three fake news affairs before the printing press

1274 BCE—The battle of Kadesh

Pharaoh Ramesses II, who lived from 1303–1213 BCE, wasn’t best friends with his neighbors, the Hittites. Seen as one of the most powerful pharaohs in Ancient Egypt, Ramesses II’s reputation as an incredible general suggests what happened next.

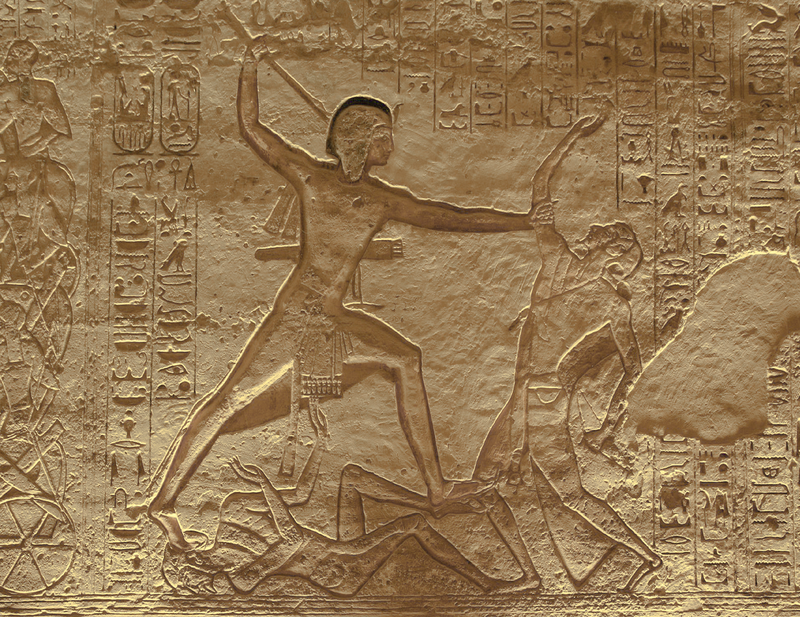

The battle at Kadesh, fought near the modern border between Lebanon and Syria, went down as the historical Egyptian victory over their adversaries of the Hittite Empire. Not only did the Egyptians win, but some inscriptions even tell the story of Ramesses doing most of the fighting by himself. After the battle, Ramesses ordered the production of two texts about the victory, which he circulated far and wide as inscriptions on buildings—including reliefs for the illiterate—and on papyrus.

Modern-day historians are not so sure about Ramesses II victory, however, even debating whether to call it a draw or a loss. The Hittite territory wasn’t occupied by the Egyptians after the battle, and it would take 15 years for the two empires to sign a peace treaty which didn’t mention a victory of either side. In private letters between the Hittite king and Ramesses II, the former asked why Ramesses was treating the battle as an Egyptian victory. Ramesses answered that the battle had indeed been tough on both parties.

Archeological evidence also casts doubt over Ramesses II’s exploits on the Lybian side of the Egyptian Empire. Rather than finding traces of war, evidence suggests that Egyptians were herding cattle and harvesting crops deep in Lybian territory—something that would have been very unlikely during wartime.

Relief in temple of Ramesses II, Abu Simbel: Ramses II slays an enemy while he tramples on another in the battle of Kadesh in 1274 BC.

32-30 BCE—Octavian versus Mark Anthony

Julius Caesar’s adopted son Octavian and Caesar’s former commander Mark Anthony battled it out over the question of who would be Caesar’s rightful successor after his murder. Octavian had a lot of power in the west of the Empire, including Rome. Mark Anthony was the most powerful player in the east of the Empire.

They didn’t just use weapons to fight their battles. Octavian accused Mark Anthony of not respecting Roman values, pointing at his lavish lifestyle in Egypt and his affair with Cleopatra, in addition to being a drunk. He also presented a document to the senate—it is still debated whether the document was legitimate or not—claiming it to be “the will and testament of Mark Anthony”. The document said that Mark Anthony wanted to be buried in the mausoleum of the Egyptian pharaohs in Alexandria, Egypt, instead of Rome. It also promised large swaths of land to his children with Cleopatra.

Octavian hoped to convince the people that Mark Anthony wasn’t a fit succesor to the great Caesar. He used poetry and slogans on coins to spread the rumors. But it was his speech that convinced the Senate to declare Mark Anthony a traitor and start a war against Cleopatra and him.

The war of Actium would be the last war of the Roman Republic. It ended when Octavian besieged Mark Anthony and Cleopatra in Alexandria, Egypt, where the two committed suicide. Octavian went on to become the first emperor of the Roman Empire, changing his name to Caesar Augustus.

1475—The boy Simonino

Although the mechanical printing press had been invented by this time, it did not yet play a role in this story. When a baby boy by the name of Simonino disappeared in the city of Trent, modern-day Italy, priest Bernardino da Feltre knew who did it: the Jews!

The priest was convinced that they murdered the child to drink its blood during Passover and preached the news from his pulpit. Many Jewish people were arrested and fifteen were burned at the stake for the crime. There was somewhat of a problem, however. The entire story was untrue!

When the papacy realized what was going on in Trent, they tried to stop the atrocities committed against Jewish people by sending a representative to the city. But local authorities doubled down and made up even more horrific stories accusing Jewish people of all kinds of evil acts. They even declared the boy Simonino a saint and attributed a hundred miracles to his legacy.

To this day, there are anti-Semetic people who claim that Simonino was killed by the Jews.

Exercise (20 minutes)

The three pre-printing press stories have something in common: all of them involve elements of fake news. During this exercise, students will analyze the stories.

- Divide the class in 6 or 9 groups

- Assign the three example cases to the groups. Make sure that every story is assigned an equal number of times.

- Groups answer the following questions about their case. They are encouraged to do additional research

- Who was spreading the story?

- How were they spreading the story?

- What goal were they trying to achieve by spreading this story?

- How successful was the attempt at reaching this goal?

Discussion questions (optional)

- Why were the powerful better able to produce fake news than the common people?

- What were the differences between the three fake news affairs?

- What were the similarities between the three fake news affairs?

- Which fake news affair do you think was the most successful and why?

- Which fake news affair do you think was the least successful and why?